First published 12/08/2012

What does learning to surf have to do with property investing? Well, lesson number one for anyone dipping their toes in the water for the first time is if you want to ride a wave, you have to get out in front of it.

Riding a wave in property works pretty much the same way, and a concept known as the ‘ripple effect’ is helping some of the pros stay out in front.

Booms typically have their start in the prime areas, and send ripples out to neighbouring suburbs as priced out buyers look for the next best thing. Savvy investors can get a lift from these waves if they can identify how to hitch a ride before they pass on by.

“It’s definitely one of the most simple, and predictable, principles that an investor can follow to ensure better than average growth,” says Real Estate Investar’s David Hows.

From ‘best suburbs’ to ‘next suburbs’

Hows says investors might want to rethink what they take away from the many ‘Best Performing Suburbs’ reports that come out each year. “So many people read in the paper and they see the top suburbs for growth over the past year and they think, ‘Fantastic, I’ll go and invest there’,” he says. “But the danger is that they have had their growth or they’re at the end of their growth and worse still maybe you will pay too much at the top of the market.”

“Look at what’s next, and not what has been.”

Because of the ripple effect, Hows says, next up are very likely those nearby suburbs that haven’t had the same level of growth, but share many of the lead suburb’s characteristics.

“It’s a real thing,” says Terry Ryder of hotspotting.com.au, “and if people are willing to do a bit of research and then look next door, or down the way, and say this area has similar qualities but hasn’t shown the same growth in the last 12 months, I think it’s next.”

Counting on uneven growth

Jeremy Sheppard, research director at property firm Redwerks, says the ripple effect occurs because price growth in an area does not happen evenly. You will often see growth start in the CBD, or perhaps, he says, in an area benefitting from a new train station or emerging café culture.

“So whatever happened in that suburb to make it more attractive so that there was this sudden spike in growth, people at some point are going to be willing to be just close enough,” he says. “Maybe they can’t afford the suburb anymore or maybe the market’s just so tight that they can’t get in so they choose the option that is near enough.

“But as you get further away then there is less and less of that near enough quality in the outlying suburbs,” he says.

“I kind of compare it to buying a ticket at a concert,” says Investar’s David Hows. “You say, ‘I really love this band and I am happy to pay $350 to sit in the front row’. If the seats a few rows back are $200, you’re likely to say, ‘well for an extra $150 I’m willing to go blue chip because I get that extra benefit’.”

But once the difference in price between the front row and the b-grade seats gets significantly larger, concert goers are more likely to give up that vaunted chance to be close enough to be spit on by their idols.

“Then, the additional value that I’m getting for the additional cost isn’t as good as I’d like, and so I’m willing to go with a seat a few rows back,” says Hows. Furthermore, as those previous front row buyers move into the cheaper seats, there is more competition for those seats and in an open market their price would get a boost.

Ride the ripple

Investors have managed to get good rides out of the ripple effect over the past decade in suburbs across Australia as homebuyers fled the epicentres of the country’s small and large-scale property booms, deciding that the suburb down the way was good enough.

Redwerk’s Sheppard keeps an eye on the ripple effect through several indices he puts together for clients, but he does caution against making a buying decision solely based on the perception that a suburb appears to be in the path of a ripple. For starters, he says, the most viable suburbs may not be the ones right next door.

Either the ripple may have already passed by, or that particular suburb may not have what buyers were looking for in the leading suburb. So investors, he says, should look more deeply at the specific growth drivers behind the ‘hub’ suburb’s surge.

“The problem that most investors are going to face is they are going to look at a map and go to the next suburb and see that it is pretty much the same growth chart,” he says. “They might need to go out for another two or three layers of neighbours in order to see an emerging trend,” he says.

He says it is especially important to identify the drivers of growth, paying particular attention to whether the neighbour has features like good access to quality schools, leisure facilities , health care, transport and infrastructure. “The neighbours with the most similarities to the source of growth are the ones most likely to get a higher share of that ripple”

Case in point: Balmain’s ripples

Sheppard points to Balmain’s rise as a blue chip Sydney suburb during the last decade as a key example of how the ripple effect can sweep up nearby suburbs. The gentrification of Balmain began around 2000 and started what would be the transformation of Sydney’s inner west.

Terry Ryder says Balmain quickly gained an identity as a hip and comfortable place to live, translating into massive median price growth. “It used to be a working class suburb and people started to realise that it is full of these terrace style homes with lots of character but close to the city and people bought and renovated and the area got gentrified, the café culture moved in and it became trendy,” he says.

“And so then people started to look for alternatives and Western Sydney was full of suburbs that are relatively close in and have since been discovered and renovated,” says Ryder.

He says the places with High Streets and character shopping similar to Balmain tended to benefit the most from the ripple effect. But primarily, Ryder says, it came down to affordability. “They looked for relatively affordable housing waiting to be renovated, and then as it started to get expensive there too, people started to look for what’s next.”

Balmain sent out several ripples that lifted its neighbours and transformed the market in Sydney’s inner west, making millions for savvy investors with the insight to get ahead of the ripple.

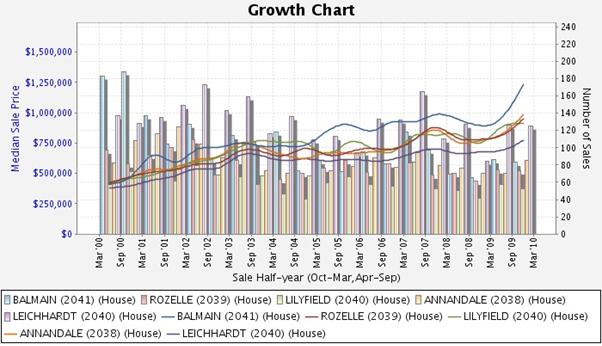

Balmain’s dramatic rise began in September of 2000, when its median home price of $410,000 was among the mid-range of its surrounding suburbs. However, over the next year the suburb posted dramatic growth of more than 58%, with a median price of $650,000, far outpacing the growth of its immediate neighbours.

An astute investor at this point would have recognised the stellar performance of Balmain, and by taking a look at a map, could have identified several surrounding suburbs that would be good candidates for growth simply because those interested buyers would be looking for an alternative after being priced out of Balmain, but on the hunt for something similar, says Redwerk’s Jeremy Sheppard.

Balmain at just 5km from Sydney’s CBD was a clear epicentre of growth for the region back in 2000, and David Hows says there were clear signs that its neighbours were poised to benefit from the ripple effect.

“What happens is if you look at blue chip suburbs around city centres there is not an abundance of land available,” he says. “So, even if there are rising rents and rising prices there isn’t a lot of land that developers can suddenly develop heavily or over develop.”

Balmain’s dramatic rise from 2000-2001 sent ripples through the suburbs to its south and west, where existing suburbs had the preferred ingredients of affordability, similar housing stock and High Streets that showed potential to draw a similar type of café culture that made Balmain so prized.

The growth of Balmain’s immediate neighbours lagged by about a year on average, with median home prices in several of the most similar suburbs - Rozelle, Lilyfield and Annandale – basically catching up with Balmain two years after its initial boom.

Redwerk’s Jeremy Sheppard says that is a pretty common phenomenon, and that often you will see the neighbours close the gap completely – a related phenomenon he refers to as neighbour price balancing. But Sheppard says the ripple effect can often work in reverse as well as the rising prices in the areas surrounding the initial hub of growth might cause it to start looking more affordable after all.

This effect may have been at work when Balmain’s second push began in 2005 when it again separated itself from its neighbours with several years of nearly 20% annual growth. Investors mindful of the ripples would have been well served to snap up properties in just about any of Balmain’s neighbours during this time, as dramatic price growth also occurred, but lagged by an average of 12 months.