There's been a great deal of discussion about whether the property market has recovered. Some experts claim another boom is on its way, while others predict that a gradual return to growth is more probable. A few are even calling the recent rise in prices a ‘dead cat bounce’, predicting that further price falls are not far away.

No matter which of the theorists turn out to be right, investors have a second string to their bow – cash flow – which will assure them of a steady source of income even if prices don’t rise.

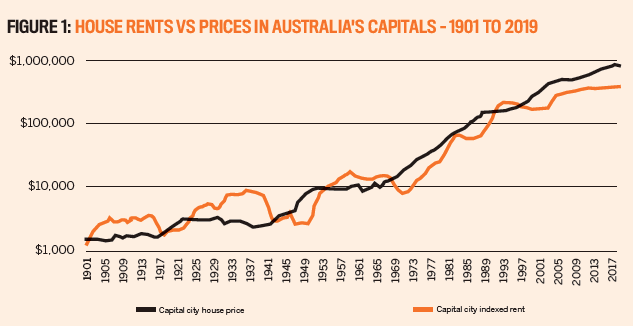

In fact, history shows that when house prices have stagnated, or even gone backwards, rents have usually risen dramatically at the same time. This is demonstrated in Figure 1, which shows the average indexed annual house rent in Australian capital cities compared to the average house price all the way back from 1901 to now.

You will notice that house rents (the red line) rose dramatically at times when house prices (the black line) failed to go up at all, such as during the Great Depression from 1930 to 1936 and the post-war migrant boom from 1951 to 1969. This is because, at those periods in our past, new households could not obtain housing finance and were forced to rent instead, which tended to push rents up.

Rents or prices have always gone up

Figure 1 also clearly indicates that prices rose in our capital cities when rents stagnated, such as during the years immediately after each World War (1918–1920 and 1946–1950), when returning soldiers were given affordable War Service Home Loans to buy properties and start families.

This brief snapshot of our property market’s historical performance shows us that when prices failed to rise, rents went up, and if rents increased, prices usually did not.

There were also significant periods when rents and prices both rose, but the only two periods in our history when both prices and rents fell at the same time were during the Great Depression and the 1960s Credit Squeeze.

These events were both preceded by bouts of excessive housing construction, which were followed by years of lower housing demand.

Jump to the present and we see that house prices have fallen in most capital cities over the last year, and in some cities such as Perth, Adelaide and Darwin they haven’t gone up for many years, but capital city rents haven’t been rising in any of them. Does this mean that developers have been building too many dwellings too quickly, leading to temporary oversupplies in our capital cities?

Overdevelopment leads to stock overhangs

Property market booms such as we have recently experienced in Sydney and Melbourne lead to a rush of new housing projects. These usually start a year or two into the boom phase, when developers are motivated by recent price growth. Investors are attracted to buying these new properties because they expect the price growth to continue. They are also offered purchase inducements by sellers’ agents and project marketers, such as low deposit bonds and rent guarantees.

The longer a housing boom lasts, the greater the number of new developments, which are mostly high-density units sold off the plan. When the growth period ends and demand slows down, the rate of construction of new dwellings starts to exceed the demand for them, and developers are left with a backlog of unfinished and even unstarted projects, to which they are committed. This is when oversupply occurs and both prices and asking rents fall, particularly in the more heavily developed suburbs.

Property market booms, such as we have recently experienced in Sydney and Melbourne, lead to a rush of new housing projects

While such periods of property oversupply are fairly rare and short-lived, that is exactly what our major urban markets have been experiencing for the last two years.

However, while the rate of housing development lags behind demand, it does eventually slow down, and this has actually occurred. The current rate of new housing construction in Australia has reached a six-year low, so the overdevelopment crisis may be nearing its end.

The other historical cause of a joint fall in both house prices and rents has been a decrease in housing demand following this type of overdevelopment boom. If we are about to enter such a phase, then there is no real prospect of rents or prices rising in the near future.

On the other hand, if our population continues to grow, then we can be sure that rents or prices or possibly even both are about to rise again.

Population growth now at record high

Population growth is an important dynamic in generating housing demand, for the simple reason that we all need a place to live.

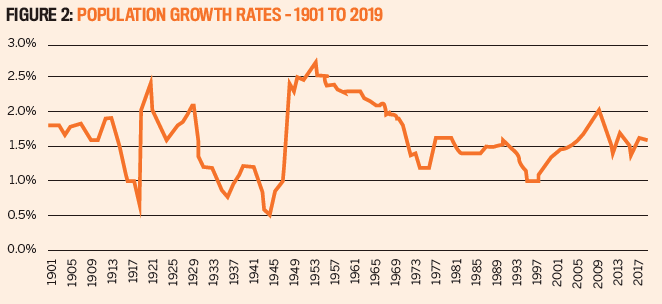

This demand could be for rentals or owner-occupation, for units or houses, but as long as our population grows, we need more dwellings. Figure 2 shows the annual population growth rates of our capital cities since we became a nation in 1901.

This growth rate has varied from slumps during the two World Wars to highs in the years immediately after they ended, but the important thing is that our population has always increased. We have the highest annual national population growth rate of all western nations, at 1.6%, and it is obvious that the cause of our sluggish house market performance is not a lack of demand for housing but too much supply.

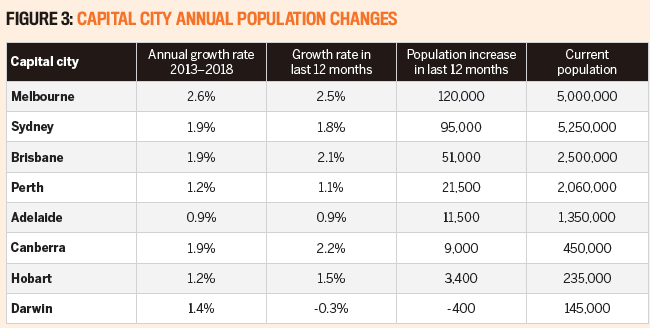

While our national population growth is currently 1.6% per year, the growth rates of our three biggest cities – Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – are much higher, as Figure 3 shows.

Such high rates of population growth have not been experienced in those three cities since the population explosions of the post-war baby boom years from 1948 to 1969. Australia's new residents are also showing a clear preference for big-city living, and the reason for this is that most of our population growth (around 65%) comes from permanent overseas arrivals.

Many of these new residents prefer living in the big three cities because they offer immediate employment, accommodation and have good public transport facilities. They also have ethnically friendly communities where new arrivals can shop, worship and educate their children in accordance with their social and religious customs.

Permanent arrivals are now coming from countries such as Iraq, Syria, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Sudan, Nigeria and Ethiopia, but despite their diverse countries of origin, virtually all overseas arrivals have one thing in common – they need a place to live.

Because they can’t usually buy a property on arrival, migrants rent for some years, until they are well enough established to obtain a housing loan and buy their own home.

Rental yields too low?

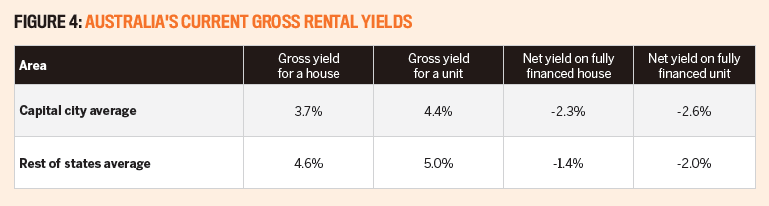

All of this would indicate that investors in the cities sought by new arrivals should also be obtaining high rental yields, but that’s not the case – not yet, anyway, as Figure 4 shows.

The reason for the low rental yields is that the amount of recent overdevelopment has led to stock overhangs of rental properties. The surplus of rental vacancies keeps yields at their current low levels, and without the prospect of regular capital growth, many investors are simply putting their money into shares or commodities that can provide better returns.

However, the large rise in demand for rental accommodation from overseas arrivals will soon combine with the reduction in new housing approvals and lead to a shortage of rentals. This is when yields will begin to rise and offer investors positive cash flow.

Property market booms, such as we have recently experienced in Sydney and Melbourne, lead to a rush of new housing projects

The positive cash flow tipping point is reached when the cost of holding a rental property, such as maintenance, repairs, rates, services, land tax, property management fees, insurance and loan repayments, is less than the income from rent. For most properties, this requires investors to obtain a rental yield of at least 6%.

Figure 4 shows that the average yield is well below this, so cash flow seeking property investors are looking at boutique shortstay rental solutions, such as Airbnb, high-res and holiday group rentals.

Stats out of kilter – and higher yields forecast

While such active rental strategies might appeal to some investors, others prefer a more passive approach to property investment, and the good news is that the stats are out of kilter. Capital city rental yields have averaged around 11% since 1901, but more recently the average rental yield for a capital city house has dropped to only 4.3%.

Yields are way below their historic long-term averages, but lower numbers of new housing developments, combined with an increase in overseas arrivals, mean that the demand for rentals will soon start to exceed the availability of suitable stock.

This is likely to occur first in the capital city suburbs most sought after by new households, and it won’t be very long before investors will enjoy long-awaited cash flow booms in those areas.

John Lindeman is a property market author, educator and commentator