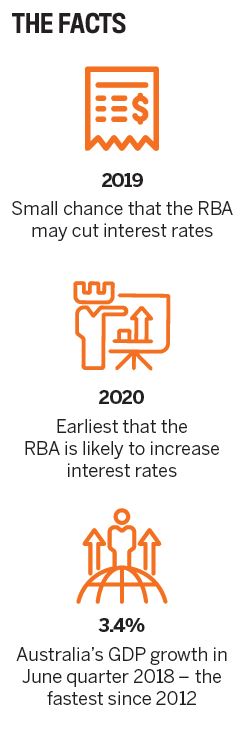

Investors might have noted some recent positives in the Australian economy. June quarter GDP growth of 3.4% was above potential and the fastest rate since 2012, while business investment has been looking healthier and infrastructure investment and exports have been supporting growth.

We have seen pretty good job numbers: the unemployment rate is trending down and is now at a six-year low of 5.3%. Job ads, job vacancies and employment surveys have also been solid. While growth in job vacancies slowed to 0.6% in the three months to August, vacancies are up 16.5% for the year and remain high. That will probably prevent a rise in the unemployment rate.

But investors must put those positives into context when assessing their impact on the Reserve Bank’s likely next move on interest rates.

Firstly, while an unemployment rate of 5.3% isn’t bad, Australia is still suffering from a very high level of underemployment. If you add underemployment (currently at 8.1%) to unemployment, our total labour market underutilisation is running at around 13.4%.

That is not only historically high for Australia but very high compared with the US, which is running at around 7.4%. We still have a lot of slack in our labour market.

The second point to make is that the RBA has another problem: uncertain consumer spending largely due to falling house prices in Sydney and Melbourne. We believe more falls in Sydney and Melbourne are likely in the next two years due to tighter lending standards and rising supply. Falling house prices drag on consumer spending because people feel less wealthy.

In light of the labour market slack and falling house prices I find it hard to see the RBA raising interest rates. We do have a rate hike pencilled in for some time in 2020, but we certainly don’t expect a rate rise in the last quarter of 2018.

Indeed, there is a small risk that at some time in 2019 the RBA may have to cut interest rates again. This is not our base case, but we can’t rule out the risk that rates might have to fall a bit further if weakness in the housing sector feeds through to the broader economy and threatens inflation on the downside.

Weakening home prices will weigh on household wealth, which in turn will constrain consumer spending at a time when the household saving rate is at an 11-year low and wages growth remains very weak. This in turn is likely to keep inflation constrained at the low end of the RBA’s 2–3% target.

So, putting all this together, growth is likely to slip back to around 2.5–3%, which is less than the Reserve Bank is expecting at a time when inflation is likely to remain low. While we believe rates will be on hold for some time yet, well out to 2020, we can’t rule out another rate cut from the RBA if the fall in house prices intensifies to the point that it further threatens the inflation outlook.

Shane Oliver

Shane Oliver

is AMP Capital’s chief economist

and head of investment strategy,

as well as being an adjunct professor

of economics at Macquarie University