Two years ago, some (mainly foreign) commentators were convinced Australian housing was in a bubble that was in the process of collapsing as the Chinadriven mining boom faded. Instead, lower interest rates have led to the usual response of rising house prices and approvals for new homes. But has it gone too far, taking us into another bubble?

Great news for the economy

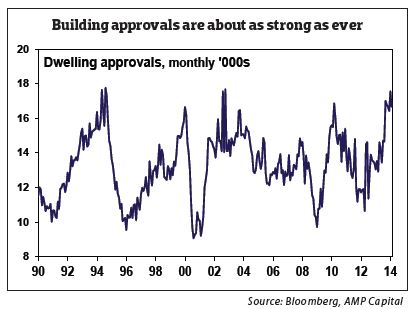

While it took a bit longer than usual, the housing sector has responded just as it should to lower rates – lower interest rates led to improved housing affordability, which has contributed to increased home-buyer demand (housing fi nance is up 23% year on year and new home sales are up 40% from their September 2012 low). In turn, this has led to higher house prices, which has signalled to home builders that it’s time to build new homes – building approvals are now about as high as they have ever been, pointing to a construction boom on the way.

In addition, rising house prices, which boost wealth, and stronger housing construction are positive for retail sales. This is all good news, as a stronger housing sector is critical if the economy is to rebalance away from mining investment.

But is it turning into bubble trouble?

While a housing recovery is necessary to rebalance the economy, a concern is whether it’s becoming another bubble. The home-buyer market has started the year strongly, with auction clearances high and house prices surging. According to RP Data, house prices in capital cities are up 10.6% over the year to March, with Sydney home prices up 15.6%.

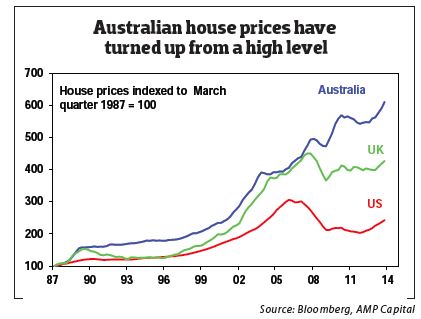

Property prices are on the rise again in other comparable countries, such as the US and the UK. The trouble is that Australian house prices are turning up from a high level.

Asset price bubbles normally see overvaluation, excessive credit growth and self-perpetuating exuberance. On these fronts, the current readings for housing are mixed.

Australian housing is overvalued

While real house-price weakness through 2010 to 2012 saw this diminish, the problem has returned again with a vengeance:

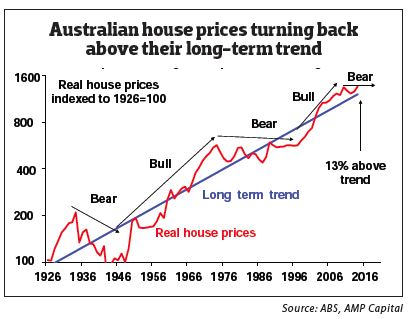

- Real house prices are 13% above their long-term trend.

- According to the 2014 Demographia Housing Affordability Survey, the median multiple of house prices to household income in Australia is 5.5 times versus 3.4 in the US.

- The ratio of house prices to incomes in Australia is 21% above its long-term average, leaving it toward the higher end of OECD countries. This contrasts with the US. On the basis of the ratio of house prices to rents adjusted for infl ation relative to its long-term average, Australian housing is 27% overvalued.

So Australian house prices meet the overvaluation criteria for a bubble. Other criteria are less clear, though.

Credit growth is a long way from bubble territory

Over the year to February, housing-related credit grew 5.8%. This is up from recent lows, with 7.6% growth in credit for investors leading the charge. But it is pretty tame compared to 2003-04 when housing-related credit growth was running at 20% plus and 30% for investors. Related to this, we have yet to see much deterioration in banklending standards.

The self-perpetuating exuberance that accompanies bubbles seems mostly absent at present:

- House-price strength is not broad-based. While prices in Sydney (+15.6% year on year) and Melbourne (+11.6% year on year) are very strong, in every other capital city they are up 5% or less. Related to this, there has been only one year of strong gains, whereas the surge into 2003 ran for seven years.

- Australians don’t seem to be using their houses as ATMs at present (that is, where mortgages are drawn down to fund consumer purchases and holidays). Rather, they still seem very focused on paying down debt.

- We are yet to see property spruikers out in a big way.

- There is little sign of buyers rushing in for fear of missing out.

- The cooking shows are still outrating the home-related shows on TV!

For these reasons, I don’t think it’s a bubble yet. However, the acceleration in price gains means the risks are rising.

What’s to blame for high house prices?

Whenever house prices take off and affordability deteriorates, there is a tendency to look for scapegoats. A decade ago it was high immigration and negative gearing. Now it looks to be foreign buyers (from China), self-managed super funds and, as always, negative gearing. However, none explain the relative strength in Australian house prices:

- Foreign and SMSF buying is no doubt playing a role in some areas but looks to be relatively small overall. Chinese interest in Sydney seems to be concentrated away from suburbs linked to first-home buyers.

- Such simplistic explanations ignore the fact that when interest rates go down, Australians borrow to buy houses and prices go up. We don’t need to resort to foreigners to find a reason house prices have gone up.

- Negative gearing has been around for a long time. It was removed in the 1980s but was reinstated as it was clear its removal worsened the supply of dwellings. Restricting it for property would also distort the investment market as it would still be available for other investments.

Rather, the fundamental problem is a lack of supply. Vacancy rates remain low and there has been a cumulative construction shortfall since 2001 of more than 200,000 dwellings. The reality is that until we make it easier for builders and developers to bring dwellings to market – and hopefully decentralise our population in the longer term – the issue of poor affordability will remain.

Implications for monetary policy

As things currently stand, the risks to financial stability flowing from the surge in house prices are more than balanced by sub-trend economic growth, falling mining investment and risks to Chinese economic growth. As such, it remains appropriate for the RBA to keep interest rates on hold at 2.5% for now. However, our expectation is that the RBA is likely to step up its jawboning of the home-buyer market by warning buyers not to take on too much debt and not to expect everrising prices, ahead of a move to increase interest rates probably starting around September/October, once economic growth has started to pick up.

While talk of so-called macroprudential controls, such as limits on loan to valuation ratios for mortgages heating up, the RBA would probably prefer to avoid such retrograde approaches (they didn’t work in the days pre-deregulation) in favour of jawboning and an eventual rate hike.

Against this backdrop, we expect further gains in house prices but at a slowing rate over the remainder of the year, particularly once interest rates start to rise again. Longer term, the overvaluation of Australian housing will likely see real house prices stuck in a 10% range around the broadly flat trend that has been evident since 2010. This is consistent with the 10 to 20-year pattern of alternating long-term bull and bear phases seen in real Australian house prices since the 1920s (see the fourth chart in this article).

Housing as an investment

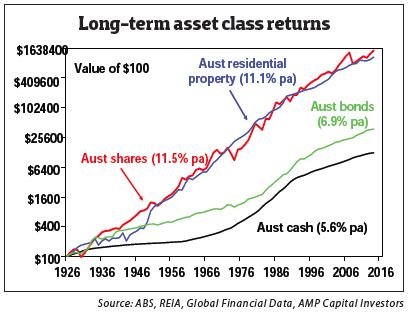

Over long periods of time, residential property adjusted for costs has provided a similar return for investors as Australian shares. Since the 1920s, housing has returned 11.1% pa compared to 11.5% pa from shares. Both have been well above the returns from bonds and cash.

They also offer complementary characteristics – shares are highly liquid and easy to diversify but more volatile, whereas residential property is illiquid but less volatile and shares and property tend to be lowly correlated to each other. As a result of their similar returns and complementary characteristics, there is a case for investors to have both in their portfolios over the long term.

Concluding comments

The recovery in the housing sector is playing a key role in helping to rebalance the Australian economy. However, while the recovery of house prices does not appear to have entered bubble territory yet, the risks are rising. The RBA’s first line of attack is likely to be more intensive jawboning, warning home buyers not to get too giddy in their house price expectations and not to take on too much debt. Later this year, though, this is likely to be followed up by a couple of interest-rate hikes, all of which will

likely see house-price gains slow.

Shane Oliver is head of investment strategy and chief economist at AMP Capital.

This article was published in the June 2014 edition of Your Investment Property magazine. You can subscribe to the magazine here.