Would you like to learn more?

The Author of this article, Anton Flynn, is a development manager and strategist for FLYNN Subdivision experts based in Perth, Western Australia. He has written a 225 page guidebook, The Infill Developer: a Concise Guide to Small Lot Subdivision and Development in Western Australia, and has also put together a correlating 14 module online course on infill property development in Western Australia.

Identify your objectives as a developer

For many people the objective in property development is to make money. It is certainly not to lose money. You only want to be committing yourself to profitable projects. To determine if projects are going to be profitable, you need to learn how to do effective and accurate feasibility studies. This article will explain the feasibility study process in detail, the input data required and how to interpret the data in a feasibility study for decision-making purposes. Learning this process is critical to your success as a property developer- if you get the numbers wrong you could sustain a large financial loss.

To determine if a feasible design solution exists for a property development site, you need to do some research and perform due diligence by way of feasibility studies. Your proficiency at undertaking them and your appreciation of their importance for decision making purposes is vital to your success as a property developer. Proper feasibility analysis takes time, expertise (yours or hired) and will cost some money. Once you have whittled down site options to a few favourites based off early investigation, it is quite possible to spend $2000-$5000 or more on detailed feasibility for a site prior to purchase. The outcome of that study may mean you withdraw from the purchase, but its better than working out you are running at a loss halfway though when its too late to stop.

Steps to consider for property development feasibility

To this end, it is important to ascertain if a feasible design solution with a healthy indicative Return on Investment exists before you commit to a development. This means doing the maths before we purchase a property, not after we have purchased it. This point cannot be emphasised enough. If you are not willing to invest time, effort and money into performing feasibility studies on sites before you commit to a purchase or develop them, property development is not a business that you should pursue.

To ascertain what feasible design solutions (if any) with healthy indicative returns exist on a site you are looking at, you must perform feasibility studies for the proposed development. Important outcomes of the feasibility study:

- The feasibility study should show a Return on Investment (also called Return on Cost) of 20% or more, given the level of risk involved in property development (small two lot splitters/battle-axe developments with a 12-15% ROI may be acceptable). It must be high enough to buffer against market change (revenue is a forecast based on current sales data) and project costing errors. If 20% falls to 15% when the project is finished (actual figures) it is not ideal but no one is losing money. If we are starting at 10-12% for a large, risky project, and it falls to 5-6% because of market conditions the deal treads a fine line, with a higher risk of losing your money. Simply put, there is not enough buffer for error and change in conditions.

- There may be one, multiple or no feasible design solutions for the site in question in the current market environment.

- Feasibility studies effect a go-no go decision. They provide a forecast based on an educated opinion of probable project costs and revenue. Final numbers may differ - they are a decision-making tool only. You are using feasibility studies to find a development site with enough “fat in the deal” to proceed with the project.

Understand the feasibility study process and input data

There are so many development opportunities out there; how do you know which one to choose? We do this by performing two stages of feasibility studies:

- Prefeasibility studies (no cost, takes a few hours), followed by

- Detailed feasibility study on the best option/s (these studies will cost money, and will take a few weeks)

Because detailed feasibility studies cost money and take time, it is important to whittle down the choices early to as few selections as possible. Generally, you’ll have a number of sites you are looking at in a given suburb (driven by the acquisition metrics discussed previously). To narrow down the choices, start with a desktop research ‘prefeasibility’ study for each site you like.

Each prefeasibility study should take no more than a few hours on a desktop. The aim is to investigate potential design constraints such as utility access considerations, site conditions/dimensions/slope, relevant planning policies that affect the site and the local market by way of a Comparative Market Analysis. This allows us to identify problems for each site, and to establish a rough order of costs, revenue and profit.

The aim of the comparative market analysis is to create a shortlist of what product has sold well in an area (to determine what product there is demand for) and investigating why. Knowing this ‘why’ will guide what you have to produce as a developer (target specification and dwelling type). During the comparative market analysis phase, research all suitable dwelling types for the site separately and compare them (i.e. 3x2 dwellings, 4x2 dwellings, single and two storey variants of both).

Although this means you may have to prepare preliminary designs and feasibility spread sheets, for multiple design solutions for the site later on, this is a necessary process so you know you have explored all potential design solutions for the site and settled on the best one. By looking at all dwelling type possibilities early it may become apparent that there are only one or two dwelling types suited to the site from the perspective of market demand and statutory compliance.

The research you do into product types will give you an idea of potential revenue, as either:

- Unit prices per dwelling derived from sales data for dwellings in the area. Make sure dwellings shortlisted are of similar:

- Finishing specification/quality,

- Age (when were they built),

- Dwelling type (single or two storey, direct street frontage or grouped dwelling/battle-axe?),

- Location (i.e. Assess if they are fronting a suburban street or major carrier road),

- Net Floor and lot size (gross floor area and lot size).

If comparable sales you find are not ideal matches(ie. Not much sales data) you must use your judgement to either exclude them from the shortlist, or moderate the data accordingly (i.e. raise or lower valuation by deciding that a product is either superior or inferior).

- Square meter rates for land, if subdividing only (i.e. no dwelling construction). With land you would research other subdivided land parcels that were sold recently in the area, and derive a square meter rate by dividing what was paid for the lot by the total meters squared of that lot. With land it is very important to moderate based on location. Frontage to a major carrier road, lots without direct street frontage, irregularly shaped lots and lots close to negative amenity considerations will always sell for less than lots with direct street frontage that are regularly shaped and benefit from good amenity. To this end: if you are going to produce direct street frontage lots, base your valuations on other comparative street frontage lot sales, and likewise for rear strata or battle-axe lots (like for like).

You can also use your shortlist to produce some very high-level indication of construction costs for the dwelling types you have shortlisted. To obtain a high-level costing present the standout selections (the ones you are going to use a as target specification to drive design) for each dwelling type shortlisted. Then present these to some builders. Ask the builders to provide an indicative turnkey construction price as a cost per square meter gross floor area ($/m2/GFA) to deliver a dwelling of similar size and specification. You can then use this rate to build up an indicative cost estimate for the dwelling type/s you are investigating.

You must also perform some Desktop research into site particulars (using free Dial-Before-You-Dig service location mapping, local government Intramaps, online Local Planning Policies and Scheme Text documents etc) to determine:

- Site cost constraints like slope and servicing/utility locations.

- Local town planning constraints that may restrict design and add cost.

In summary, you can use this early market and town planning research to identify constraints that may remove some sites from the selection criteria. For those that remain on the shortlist, you can produce a very high-level indicative return on investment summary for all dwelling type options investigated for each site. You can do this by deducting the site acquisition costs, plus the dwelling construction cost estimates (based on maximum permissible site coverage for each dwelling x $/m2/GFA estimate for dwelling type from the builders), from the indicative revenue for each dwelling type, for each site.

At this point it should be apparent which (if any) of the dwelling types are worth investigating further as feasible design solutions at the detailed feasibility study stage with some preliminary design drawings, costing and valuations. There will usually be one or two clear frontrunners (sites and dwelling types for those sites) that warrant further effort and attention.

If there is one you like, proceed to the second stage of feasibility: making an offer on the property subject to due diligence at your absolute discretion.

Give yourself 2-4 weeks (dependant on the time needed to collate specific types of data) as a condition of offer to perform a detailed feasibility study on the site. This must include site access (you may need to negotiate a specific number of site visits). This gives you the option to withdraw if further research indicates proceeding is not viable.

This is a very important step; if the seller will not accept a due diligence period do not proceed with an offer. Alternately, you could make an offer “subject to finance” (similar time period) and perform a detailed feasibility study in this time; however, this may limit your ability to gain site access, as this would not usually be needed for finance. Site access will be necessary if you need to do site inspections, surveys or soil testing.

A Detailed feasibility study will require input data and time (2-4 weeks as noted) to determine an accurate order of costs and revenue forecast. Suitable input data will vary from project to project. Typical input data and research activities may include:

- Comparative market analysis for revenue forecasting and design briefing (mostly complete at prefeasibility).

- Town Planning investigation (mostly complete at prefeasibility).

- Feature survey and/or dwelling concept sketches/overlays.

- Preliminary engineering investigation (geotechnical and/or civil dependant on site geography and topography).

- Producing a summary of indicative cost estimates and ROI forecast.

Evaluate real estate investment feasibility

Profit forecasts in property development (develop to sell models) are usually calculated, assessed and presented in one of three ways:

- Return on Investment (ROI)

- Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

All three are calculated differently and reflect cost data differently.

Return on Investment/Cost (ROI or ROC)

ROI = Net Profit / Total Investment * 100

Equation 1- ROI This is a simple and common way to assess a project return and is suitable for short-term projects (12-18 months). Return on Investment (also called Return on Cost) is the forecast profit divided by the sum of Total Development Costs (funded by debt and equity), reflected as a percentage.

In the infill development space, 20%+ is the ideal target. Less than 15% is not typically pursued (the opportunity cost of your money must also be considered and is better spent elsewhere).

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

ROIC = Net Profit / (Total Investment – Debt component of investment) * 100

Equation 2 - ROI Not dissimilar in calculation method to ROI, Return on Invested Capital is the forecast profit divided by the sum of Total Development Costs (the equity component only), reflected as a percentage. This reflects the leveraged return of real money invested. It is a useful tool to see how hard you can make your money work for you.

Care must be taken here; a project can have a ROIC of 35% but an ROI (on all debt and equity) of only 10%. The ROI in this scenario tells us that the margin is far too lean on this deal and our money is better invested elsewhere.

Particular caution should be exercised when a project is advertised on RIOC alone. A holistic project assessment should be made as some agents, investment groups and syndicate wholesalers will present ROIC as ROI (unknowingly or deceptively), deluding you from the real risk associated with participating in a project with a very low real return.

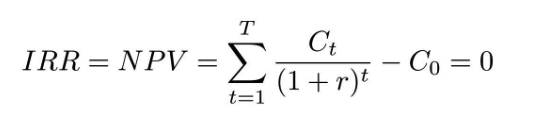

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Equation 3- IRR

IRR is defined as the discount rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows for a particular project equal to zero.

Another way to think of it is what compound interest rate would I need to apply to the total development costs over the project time period (annually) to achieve the same total revenue?

This is a complex rate of derivative calculation (it is typical to use excel syntax functions to derive the IRR). The IRR allows us to assess the opportunity cost of the investment by determining an annual rate of return to compare other lower or higher risk ventures with our cost of capital. This is typically used on large, longer projects (3+ years).

To calculate an IRR effectively and accurately that has any evaluation value, detailed cash flows (monthly) and project cost summaries are required. With infill development, the projects are short (typically 12-18 months), and there is insufficiently accurate project timeline and cost data collected during our “Offer subject to Due diligence period” (2-4 weeks) to warrant use of this method. Although this method of calculation may not be suitable for all projects the concept remains important.

Evaluate Residual Value to meet ROI

After assessing the forecast ROI in the detailed feasibility spread sheet, it may become apparent that there is an insufficient margin for the project based on the current acquisition price of the land, the total development costs and the forecast revenue.

The easiest and most logical place to find this extra margin is in the acquisition price of the development site: reduce the offer to reflect a required Residual Value to meet your ROI target.

For example, if the forecast indicates that an extra $50,000 profit is needed to make the deal stack up, offer $50,000 less for the property you are trying to purchase for the development.

Construction and development costs are mostly fixed; your market research and site constraints determine what type and quality of dwelling you have to construct. Offering cheaper, inferior product to market in order to save on costs will only affect sales negatively at the other end of the project.

Likewise, being over-optimistic and inflating sales prices in your spreadsheet without evidence is erroneous. You are only deluding yourself.

In summary, your developer margin comes from paying the right price for the site at the start. To determine what this amount is (the feasible residual land value) you have to be able to do a feasibility study of your own before you buy it. If your feasibility research data tells you that you need to pay less for a site then you need to reflect those findings on your offer to the vendor. It is a reality that many of the sites on which you will be performing due diligence will be overpriced from a development perspective. This is often the case in newly rezoned areas where owner-occupiers are the vendor and they are seeking to ‘cash in’ on the opportunity.

If property development feasibility topics such as sourcing profitable sites, feasibility considerations, input data, market research, and putting together your own professional feasibility studies (with templates provided) are of further interest to you, the author of this article explains and addresses these topics in further detail in the publication listed above.