The inability to confidently source locations with strong growth potential has turned many investors in recent years to manufacturing equity via renovations or small developments. Now that the Australian market is starting to look good in a number of capital cities, finding capital growth is going to become a little easier for some. But this doesn’t mean investors should no longer consider strategies for manufacturing equity. And, more importantly, combining manufactured equity with strong capital growth can be a double whammy for your bottom line.

What is manufactured equity?

Equity in a property is the difference between the value of the property and the propertyvalue of the mortgage over it. Building equity is essential for buying that next investment property.

Equity builds up in three ways:

- You can pay down the mortgage – which takes time and is hard work.

- You can wait for capital growth to take place – which is easy but takes time.

- You can add value via a renovation, for example – which is quick but hard work.

Option 1: isn’t often talked about because it’s less efficient at creating wealth. It is both hard work and slow.

Option 2: is often referred to as ‘organic’ growth. This is my favourite because I like the idea of sitting on my hands and accumulating wealth rather than busting a gut for it.

Option 3: is the one most people refer to as ‘manufacturing equity’. If you’re keen and have some know-how, this is a great way to force growth.

Ways to manufacture equity

There are a number of ways to manufacture equity. The most obvious ones are:

- Renovate

- Subdivide

- Develop

Renovation key principles

A renovation may, for example, involve bringing a tired old property up to scratch with a modern kitchen, a new bathroom and a fresh coat of paint.

Renovations work through the concept of synergy. That is, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. If an old property has many eyesores, the perceived value of the property may be lower in the minds of potential buyers than the sum of the costs to restore it.

Everywhere the potential buyer looks, there is a problem. This becomes overwhelming if the buyer is not able to break down the list of rectifications and cost them.

In contrast, once renovated, the perceived value of a property may be greater than the sum of the money spent to improve it. This time, everywhere a potential buyer looks there might be some ‘wow factor’.

It’s important to understand this concept of synergy when searching for a renovation project. If the investor’s thinking is that renovation profits come from doing it yourself, then all they end up doing is exchanging their time for money. It’s the same as getting a part-time job for the weekend. The serious profits are in using synergy to your advantage.

Subdivision key principles

A subdivision might involve splitting a 1,000sqm block into two 500sqm blocks, for example. Each new block can now have a house built on it. The value of the two new blocks together may be worth more than the original single block alone.

Subdivisions are another play on misunderstandings of perceived value, much like with renovations. Homebuyers may not see much extra value in a property that has extra space. A bigger backyard does mean extra space for the kids, but there is more to mow, too. The value a homeowner places on an extra 200sqm may only amount to $50,000. But to an investor planning to subdivide, it may be worth an extra $100,000.

Every additional 100sqm of space is almost a waste to the homebuyer once it exceeds their minimum. This perceived devaluing of large blocks works to the investor’s advantage so the investor can acquire these blocks cheaply. After the subdivision, the perceived value again works to the investor’s advantage. The lack of space is still a negative to the homebuyer, but it’s not a deal-breaker if they can still build a decent-sized home.

Note that a block that is exactly twice the size of other blocks in the street will have the perceived value of being exactly double the price. Similarly, a block that is exactly half the size will be perceived as being exactly half the value. Homebuyers can do simple maths, but they may struggle with abnormal or non-even multiples of block sizes. They key to a successful subdivision, like a successful renovation, will come down to recognising poorly perceived values among homebuyers for both the purchase price and the post-project price.

Development key principles

A simple development might involve knocking down a house and building a duplex. Or it may involve buying a block of land and building three townhouses on it.

The principle behind a profitable development project lies in finding underutilised land. The land may have a house on it but the council planning laws and market would accommodate a block of apartments, for example. The investor may be able to find a property that has excellent development potential that the current owner is unaware of. However, this case is unlikely since their selling agent will more than likely know of the potential.

The major reasons why sellers may not do the development themselves are lack of funds, lack of experience, lack of time or lack of interest – probably not lack of awareness. This may alter

the key principle of a successful development from recognising underutilised land to instead simply having the experience, funds or determination. Larger developments are therefore more likely to be more profitable since fewer people will be able to fund them. It also means there could be a direct relationship between success and experience.

Strategy pros and cons

Renovations are quick to do, compared to developments. The skills required to complete a renovation successfully are also relatively easier to acquire than those for a small development.

Renovations are a lower-risk strategy but also have lower returns. That means you may not be able to add as much value. Renovations are generally cheaper than developments. A lick of paint and some new flooring may only cost $10,000. But even a one-bedroom granny flat could cost many times that.

Developments require a considerable amount of money, experience and knowledge and have a higher risk. But they come with higher returns. The value-added from a development will usually exceed that of a renovation. Developments are usually much longer projects. It not only takes longer to build, but just getting approval from council can take many months.

Subdivisions are generally a little more advanced than renovations in terms of expertise required, the risk involved and the potential return. However, they are sometimes comparable to renovations in terms of time and cost. Some subdivisions can be comparable in complexity to small developments. In fact, a council will probably want to know what you plan to build on the new blocks you’re creating.

Complexities

A renovation can be major, like altering the structure of a dwelling or extending out the back, or even creating a whole extra level on top of an existing dwelling. Or a renovation can be quite simple, like a coat of paint and a general tidy-up. Similarly, a subdivision can be simple, for example\ splitting a block in half. Or a subdivision can be quite involved, such as opening an entire new housing estate. Developments can be as small as the construction of a granny flat or as large as building a multistorey block of apartments.

DIY or hire

For each of these strategies you can engage the services of a professional to take care of the project on your behalf. You pay the professional and they manage the project according to your requirements. Alternatively, you can do them yourself to save a few bucks. This DIY option has extra risk and probably less chance of adding as much value, but it may be the only option if you’re on a tight budget. Hiring a professional involves less risk, but you need more money to pay for a professional result.

Personally, I prefer to take every opportunity to work by making decisions rather than work by actually doing things. Asking someone to manage a development project for me may be more expensive, but it’s the best use of my time. I want to work smarter, not harder. The easiest ‘work’ I can do is to make a smart decision.

Project success

Success in manufacturing equity will largely come down to:

- General capability of the individual involved

- Amount of education in the area of expertise

- Amount of experience from past projects

- Amount of expert assistance used

If you do plan on doing things yourself, be realistic about your capabilities; read some books, go to a few seminars and get a mentor to maximise your chance of success.

Example renovation numbers

A typical successful renovation project might involve spending $40,000 to renovate a $400,000 house. A new bathroom and kitchen with a fresh lick of paint and new floor and window coverings could add as much as $100,000 to the value of the property. That’s creating manufactured equity of $100,000 using only $40,000. With an 80% loan-to-value ratio, the investor would have to pay a deposit of $80,000 (20% of $400,000). If they then manufactured $100,000 in equity, they could borrow an extra $80,000 (80% x $100,000 = $80,000).

Although that $80,000 would not be enough to buy another property of similar value, it would at least be a start. From here the investor would need some extra capital growth to get into the next investment, assuming they wanted to keep their renovated property.

To repeat the process the investor would need about $140,000 in total to pay for:

- $80,000 deposit

- $15,000 stamp duty, legal fees, inspections

- $40,000 reno costs

- $5,000 holding costs

Manufacturing $80,000 has got them just over halfway there. You can see that capital growth would still be needed if the investor wanted to hang on to the property and then borrow against the increased equity and buy again. If the investor sold the property for its new value of $500,000 and paid back the mortgage of $320,000, they would have $180,000 left over. But out of that amount, payments would be due for legal fees, agent’s commission and capital gains tax.

Given that the investor started with $140,000, you can see why buying, renovating and selling is quite inefficient for these types of minor DIY renovation projects. So there would be very good reason for the investor to hang on to the property after renovating, in order to give capital growth a chance to make them wealthy.

Example simple development

A simple three-townhouse project valued at $1.2m on completion might only require $200,000 of the investor’s own money. Depending on the investor’s experience, assets and income, the bank might contribute as much as 80% of the total development costs (TDC). The TDC would include costs such as land purchase, development application, consultant’s fees, legal fees, holding costs, to name a few.

A simple three-townhouse development could have TDC totalling $1m. The bank might lend as much as 80%, or $800,000, in this case. The remaining $200,000 would come from the investor – that’s their ‘hurt money’. Upon completion the townhouses might be worth $1.2m, which would give the investor a total of $200,000 in profit.

Given that the investor contributed $200,000 in the first place, this would represent a 100% return on investment. A project like this might take only 12 months if everything went according to plan. Hold-ups with council usually extend the completion date though. In some isolated cases this extension can be dramatic, perhaps doubling the timeline of the project.

Larger developments

It is generally accepted that the larger the project, the greater the profit margin. A 10-townhouse project might be worth $4m on completion but only cost $3m to develop, the reason being that many of the costs come down as a percentage of the overall project costs. Most of the bigger projects are harder for smaller developers to fund, and the banks generally will not look at the bigger projects unless the investors have significant experience or significant assets backing their project.

Passive development

Investors can overcome the barriers to large developments by pooling their funds into a property syndicate established purely for the purpose of realising the economies of scale (and profit) associated with these larger projects. If the investor does not have the experience or funding to take on a project on their own, then a syndicate can offer one solution. Syndicates are referred to as ‘passive’ development since you pretty much just sign up and provide funds and the managers of the syndicate do the ‘hard yards’ for you.

Obviously, the manager of the syndicate deserves some payment. So, although the passive nature of syndicates makes them appealing, on the downside the return on investment is reduced with this added expense.

Passive development numbers

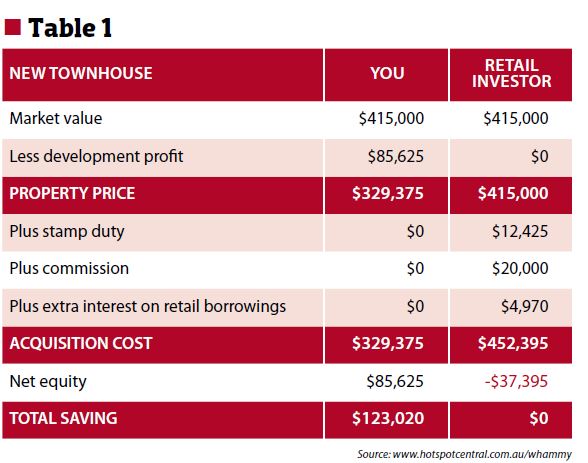

Here are the numbers, for illustrative purposes, for a project that a client of ours (a builder) recently packaged for our data subscribers. Please note the numbers are based on the investors holding their townhouses in a pack of eight on completion. Each investor contributed $150,000, with the townhouse projected to cost $312,500. A major bank put the balance of funds in. The bank ‘as if complete’ bank valuation for the townhouse was $415,000, saving the investor 25% against market value, or $102,500.

It’s worth mentioning that, in a case like this, there is also no stamp duty to pay on completion, as it is your property that is being developed. You are the developer, so there is no selling agent’s commission either. You also keep the developer’s profit margin.

Table 1 illustrates how total savings of $123,020 could be achieved. This is based on the retail price. By manufacturing equity, you buy at a wholesale price. This could mean the difference between having to stop acquiring after your first or second investment versus buying again immediately as you draw out your equity to fund the next purchase.

As with the renovation example, capital growth is still needed for the investor to hold their investment yet access equity from it in order to repeat the process. But in this case, the shortfall is not as significant.

The higher the risk and expertise of the equity manufacturing strategy you employ, the higher the profit you can expect. However, the manufacturing equity strategies simply don’t create enough equity to hang on to the investment, draw down on the equity and then repeat the process without eventually running out of either equity or serviceability.

Using long-term national average yields and long-term average interest rates in your calculations, even highly successful projects struggle to meet both cash flow and equity objectives. So capital growth still plays a crucial role for investors, regardless of strategy.

Capital growth

Combining manufactured equity with capital growth is obviously a preferred option. If your hunch about capital growth has proved poor, at least you have some manufactured equity and hopefully the opportunity to sell for more than what you paid. As I showed in the examples, it is usually not possible to get all the money you put into an investment out of that investment by borrowing against the manufactured equity. Usually a sale is necessary to release the original equity.

That means it is not possible for most investors to repeat the process without needing some capital growth after the project is complete. Too much focus purely on the project could distract investors from the merits of the location. Note that combining growth locations with manufactured equity usually eliminates the DIY option. This is because it is unlikely the investor will live near the location identified with strong growth potential. The investor will have to be close by in order to at least manage the project in the DIY case.

This means that many manufactured equity DIY projects limit their upside potential by choosing locations based on proximity to the investor rather than strength of the market. This puts greater pressure on the project to be successful and makes professionally managed projects immediately more attractive.

However, not all professional renovators and developers are willing to travel to genuinely remote locations. So, strong capital growth locations would need to be limited, even with the non-DIY option. Check with a range of professionals to see how far their service reaches geographically, and then search for good locations within that range.

Weighing it all up

Should you buy in a location where you know there is better growth potential but no opportunity to manufacture growth? Or should you buy close to home in an ordinary market so you can add value and save on costs by doing it yourself? Or should you buy in a reasonable location that is not too far from a professional developer or renovator? There is no right or wrong answer. Examine each individual investment opportunity on a case-by-case basis. I create a spreadsheet to estimate the return on investment for each opportunity. The one with the best bottom line gets my dollars.

I hope this has helped clarify some of the options available for manufacturing equity, and their key principles. I also hope it has highlighted the never-ending need to identify locations with strong capital growth potential despite using these value-adding strategies.

Jerry Sheppard is an active property investor and director of DSRscore.com.au. He is also the inventor of the DSR (Demand to Supply Ratio) Score, which measures the capital growth potential of markets based on their balance of property supply to demand.