1/08/2018

When a location enjoys high price growth, demand for that region changes. Generally, it is likely to experience less demand in the near future, because the growth puts properties out of reach of most prospective buyers. Instead, they look elsewhere for cheaper, more affordable locations.

Some experts insist that there is predictability to this progression of price rises, and they call it the ripple effect, comparing the movement of housing prices from one location to the other to the way ripples move across a body of water when you throw something in. In order to take advantage of this phenomenon, they tell us, all you need to do is predict in which direction the price ripple is heading and get in before it arrives.

You can take personal advantage of this highly reliable but little-understood effect by remembering that price ripples occur when areas of high demand become unaffordable – and the demand then spreads to other areas where prices are lower.

Price growth only occurs in these areas when demand starts to exceed supply. The theory is simple, easy to understand, and many market analysts consider the ripple effect as a given. It can come unstuck, however, if we rely on past performance when making our predictions.

.JPG)

Many predictions go astray when experts use past performance to justify them. This is easy to see when we compare the bestperforming capital cities. Every capital city has had their turn as the best price growth performer since 2002, as Figure 1 shows.

It would be foolish to forecast that Brisbane must be the next housing market to boom, based purely on the fact that it has had the longest wait – since 2003, as Figure 1 shows. However, it is easier to predict where the price ripple effect will occur within a state, because it tends to move outwards from more expensive housing markets in a capital city to the cheaper regional areas.

This is demonstrated in Figure 2, which shows how the housing boom in Hobart has rippled to Launceston, the second-biggest city, and is about to spread to other coastal towns in Tasmania as well.

In what turned out to be a good example of the price ripple, strong price growth occurred in Melbourne’s housing market during 2013 and then rippled outwards to the Mornington Peninsula the following year, as Figure 3 (overleaf) shows.

Price growth in the Mornington Peninsula was followed by price rises in Geelong in 2015 and then in Ballarat in 2016, with Bendigo being the latest Victorian city to experience price growth. Not only are each of these population centres progressively smaller in size, but they are each also progressively further away from Melbourne.

Growth may not necessarily take place in such a predictable fashion, however, because the price ripple effect can also be somewhat unreliable.

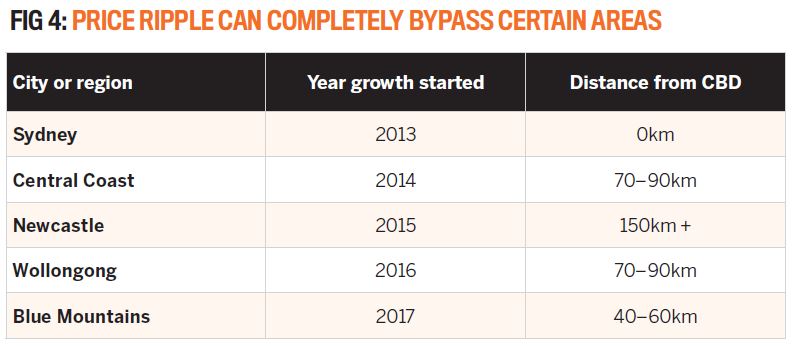

For example, the recent performance of the NSW housing market is shown in Figure 4 (overleaf), demonstrating the order in which growth started in the state’s major urban centres.

While Sydney’s high price rises certainly rippled out to the nearest housing markets, such as the Central Coast and then Newcastle, the ripple bypassed nearer areas such as Wollongong and the Blue Mountains, which should have been first in line to receive price growth after Sydney.

.JPG)

This warns us that the ripple effect can sometimes completely miss some areas, as if they are rocks in a pond around which the waves must move. Even more critical is the fact that, if there’s nothing to start a ripple, it won’t happen. Ripples in a pond are created if you throw in a rock, and price ripples won’t start unless there is a rise in demand that is enough to cause price growth. So what causes these price ripples to start?

"The housing boom in Hobart has rippled to Launceston … and is about to spread to other coastal towns in Tasmania"

Ripples begin with first home buyers

Aspiring first home buyers, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, usually find the cards stacked against them. Banks are unwilling to lend, deposits are difficult to save, and repayments are too high.

But every decade or so, everything lines up in their favour: interest rates fall, finance is easier to obtain, governments offer deposit grants and stamp duty exemptions, and it can even be cheaper to buy than to rent. This occurred in 2000 and again in 2012, and so a huge backlog of frustrated first home buyers entered the housing market. Demand increased so much that prices started to rise.

What happened next was that, as prices rose, first home buyers were forced to look for properties in other suburbs where prices hadn’t gone up yet, because their purchasing power was limited. This is how the price ripple effect starts, as aspiring first home buyers keep being pushed further outwards.

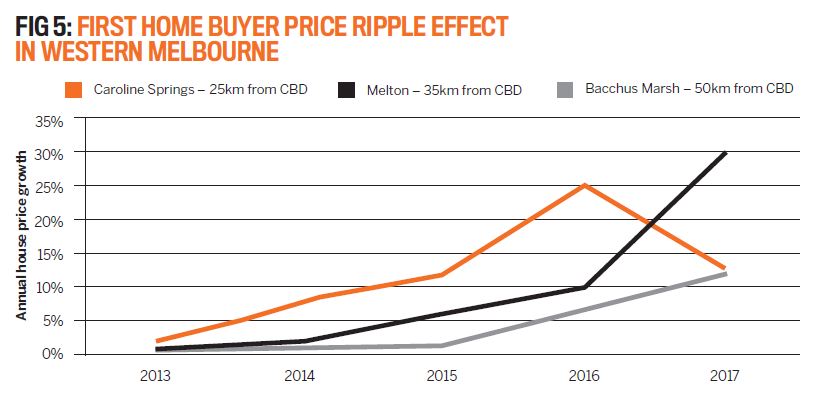

Figure 5 shows how the price ripple took place in Western Melbourne from 2013, with first home buyers forcing prices up in Caroline Springs until they were unaffordable and demand then shifted to Melton. The demand is now moving further out again to Bacchus Marsh, which is experiencing its own first home buyer price boom as a result.

Even though many aspiring first home buyers are being priced out of suburban housing markets because of the sheer weight of demand, the ripple effect doesn’t end there. In fact, it intensifies, because many of them purchase homes from former first home buyers who are in a position to use lower interest rates, easier finance and their increased equity to upgrade to bigger, more suitable homes in better suburbs.

As existing homeowners decide to upsize, another price ripple effect takes place, this time surging up through more established suburbs with increased home values that encourage more existing homeowners to upsize.

When price growth is occurring almost everywhere, investors seize the opportunity to profit from the growth that is taking place, and when enough of them participate it results in a housing market boom. This is where Sydney’s housing market was in 2016 and Melbourne’s in 2017.

Because this price boom was not in the government’s best interests, it instructed APRA and the Foreign Investment Review Board to introduce measures that curbed investor activity. The investor component of the price ripple in Sydney and Melbourne has now ended, but price ripples do not rely on investors – they end with downsizing final-home buyers.

.JPG)

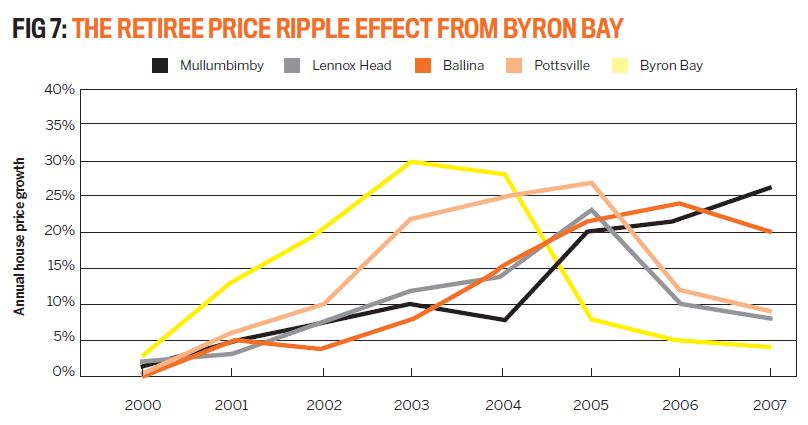

Potential retirees have waited in vain since the GFC for their share portfolios or super to rise in value, while those in Sydney and Melbourne have watched their homes more than double in value over the same time. Many take the opportunity to downsize, selling the family home and buying a house on the coast or in the hinterland where prices are much lower. This not only offers them a desirable lifestyle but presents them with a retirement nest egg. As the price ripple effect enters its final stage, prices rise in many coastal destinations while growth back in the capital city comes to an end.

When house prices in Byron Bay approached those of Sydney, retirees moved instead to nearby Pottsville and Lennox Head, then as prices there rose as well, they moved to Ballina and finally to Mullumbimby, where house prices had not yet risen. The price ripple effect, which had started in the lowest-priced suburbs of eastern capital cities in 2000, finally ended seven years later in our coastal towns.

In Sydney and Melbourne we are at the end of a price ripple – housing prices are too expensive for first home buyers, who can’t get finance, and another backlog of aspiring first home buyers is now building up. If the past is anything to go by, it could take a decade before the conditions that are favourable to first home buyers once again line up together and another price ripple starts.

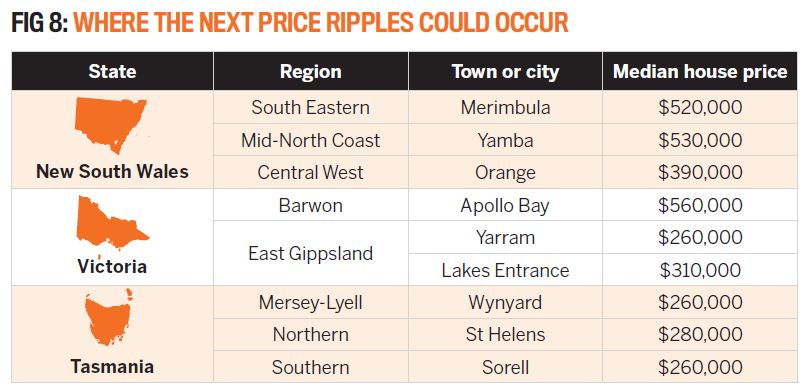

On the other hand, there is no sign at all that such a price ripple is about to occur in other capital cities or states, except for Tasmania, where it is moving from Hobart to other population centres in the island state. The areas around Australia that have the greatest potential for price ripples to occur are shown in Figure 8.

You can search for your own price ripple candidates by using these three rules:

1. Price ripples occur when areas of high demand become unaffordable.

2. The demand then spreads to other areas where prices are lower.

3. Price growth only occurs in these areas when demand begins exceeding supply.

John Lindeman

John Lindeman

is a property market author,

educator and commentator,

and director of

Property Power Partners