07/01/2019

Some experts claim that a market may be overdue for growth if there has been little to no price growth for many years, while others will assure you that the best investments are made in suburbs that have consistently performed well in the past.

Not only do these theories totally contradict each other but they are also flawed because they rely on past performance in one way or another.

Past performance isn’t always a good indicator of future performance, because the dynamics that generated price and rent changes in the past are very likely to be different in the future. There are three key dynamics that can accurately predict whether prices and rents are likely to change in the near future, and the first of these is people.

Any rise in the number of households moving into a suburb or locality causes an immediate increase in the demand for housing, because we all need a place to live. Unfortunately, this is where many predictions go astray because these new households could be renters or owner-occupiers. They may cause rents to rise but not prices, or prices to increase but not rents.

The second dynamic is purchasing power. It is the need for and ability to obtain housing finance that determines whether the housing demand from new households will be met by renters or buyers.

The third property prediction dynamic, properties, then comes into play. Rents will only rise when the demand for rentals exceeds the number of vacancies available, and prices will only grow if the number of properties listed for sale is less than the demand from potential buyers. We need to consider all three when analysing the potential for any property market to boom, and when they all line up we can be fairly certain that a boom is likely to occur.

Using the three property prediction dynamics enabled me to correctly and publicly predict that Sydney’s housing market was set to boom in 20131 , and reveal which suburbs were likely to rise first in price, and to also forecast that the Hobart housing market would boom in 20172, just before the growth kicked in.

Using these dynamics, I can now reveal which capital city is most likely to boom next, forecast when this could start, and predict which suburbs have the greatest potential to be the growth leaders.

Population growth and housing demand

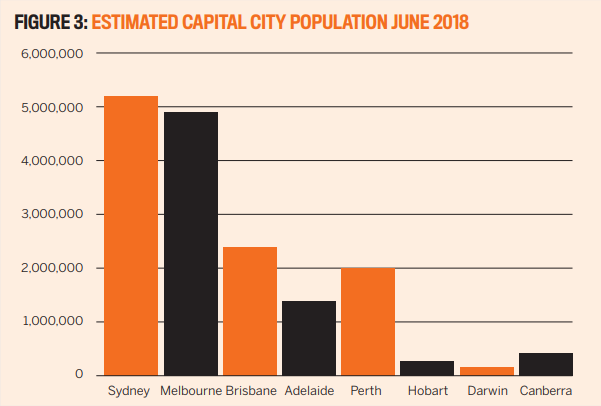

Any analysis of a property market needs to start with people. Although all our capital cities have always grown in size every year since Federation in 1901 (except for Darwin following the devastation of Cyclone Tracy in 1974), their rates of population growth have varied enormously, and periods of high population growth have always led to rising housing prices.

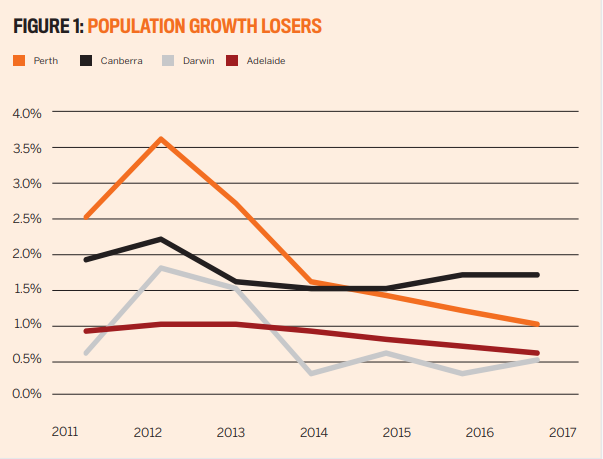

This is not a chicken and egg scenario, as the growth in households has always come first. On the other hand, cities where population growth rates are falling have not experienced the type of housing booms seen in Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart. Figure 1 shows the losers in terms of the rates of their population growth.

The biggest loser is Perth, which back in 2011 had a record-high population growth rate of 3.6%, one of the highest in our history. This has fallen to an annual increase of just 1% last year. Darwin has also suffered from a decline in the annual growth of new residents since 2011, while Canberra and Adelaide have been flatlining. We cannot expect any of these capital city housing markets to boom unless their population growth rates rise significantly in the near future.

This is not to say that housing price growth can’t occur, or that some suburbs will not boom, but simply that a general property market boom is unlikely in Canberra, Darwin, Adelaide or Perth unless and until their population growth rates lift significantly.

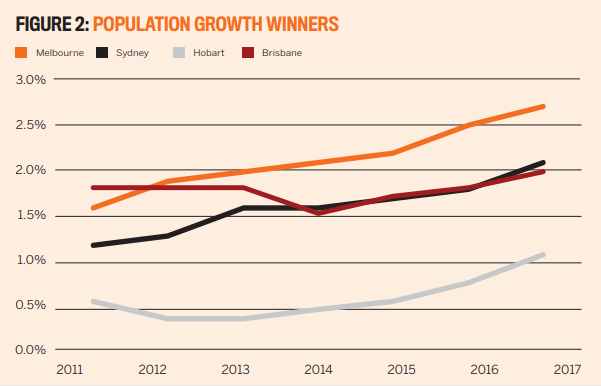

Figure 2 shows the capital city population growth winners and you can see that the rate of population growth in Sydney and Melbourne has been rising more or less continuously since 2011. The property market boom in those two cities started about two years after population growth rates rose.

Because the growth starts at the low-priced end of the market, it could remain hidden from view for some months

Purchases, not rentals

Population growth can come from three different sources, and each source has a different effect on the housing markets. The first is natural growth, which is the number of births minus the number of deaths that occur each year. The natural growth rate in Australia produces around 150,000 new residents each year, and the impact on the housing market is initially minimal as babies create demand for more bedrooms rather than dwellings. This can eventually lead to housing demand if their families need and can afford to upgrade to a bigger home, but it’s a slow process.

A far more immediate source of housing demand is overseas arrivals, of which Australia receives 250,000 each year. Not only are there around 100,000 more overseas arrivals than new babies each year, but all of these new residents need accommodation and therefore create immediate demand for more housing.

And there’s more to it than that, as most of these new residents prefer to live in our big cities and they need to rent for several years before they can afford to buy their first homes. They seek out older, well-established suburbs where there are already communities of people from similar ethnic or cultural backgrounds and the same religious affiliations. Whenever we experience a large number of overseas arrivals from a particular part of the world, we can be reasonably sure of where they will prefer to live.

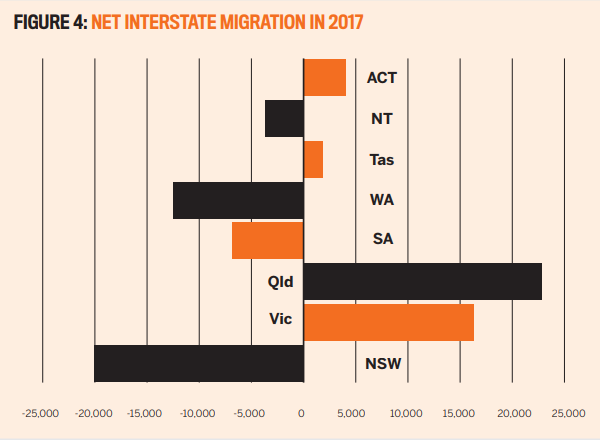

There is one more source of population growth or decline, and that’s the movement of people between states and territories. According to the ABS, an estimated 376,700 residents moved interstate in 2016/17. They have a direct impact on supply and demand, so we need to know what types of households make these interstate moves, where they go, and whether they are likely to buy or rent.

Figure 4 shows the net effect of interstate movers, and that NSW and WA are the biggest net losers. When we look at their demographics, we see that most of these movers are younger people leaving Sydney because of the unaffordability of its housing, or deserting Perth to look for employment in the eastern states. Many of them were overseas arrivals from a few years ago, who are now making their second move in Australia.

So while Sydney currently has high numbers of overseas arrivals, many of these people will eventually move to Melbourne – or to Brisbane, which has the biggest net annual gain of new households from interstate. Even Tasmania, which for many years has had a negative interstate balance sheet, has started to gain more people than it loses each year. While some of these households are retirees, the ones who move to the big cities tend to be younger people seeking their lifestyle, employment and education opportunities, and affordable housing.

We need to know whether the new households are likely to be renters or buyers, as only buyers can directly cause prices to rise

Growth starts low

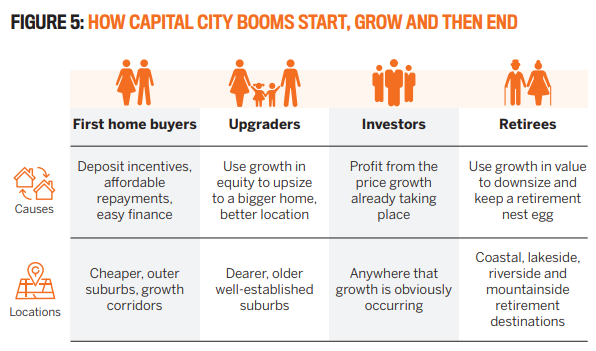

When these households start buying their own homes, they do so at the low-priced end, which is the affordable first home buyer market. Figure 5 shows how housing price growth starts with the cheapest suburbs and demand shifts up to dearer well-established suburbs as price growth motivates existing owners to upgrade.

As more and more owners decide to upgrade, investors move in to participate in the price growth, and a boom often starts. The boom ends when potential retirees decide to downgrade, using the growth in equity that they have obtained from the boom as a nest egg for the future. This is how the recent property booms in Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart all started and ended.

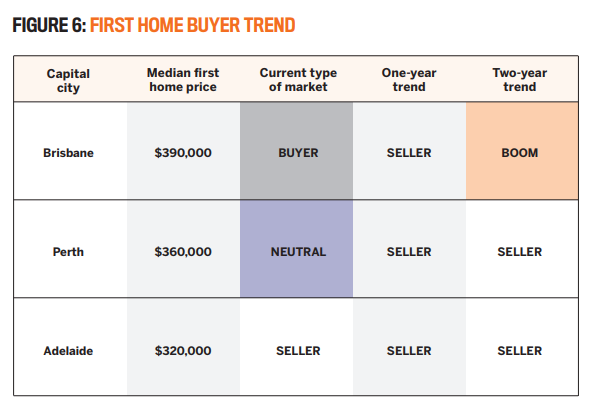

The first home buyer trend is now rising in other capital cities, but the supply of affordable first homes is still greater than demand in Brisbane, so prices in the lower-priced suburbs are not rising and it is a buyers’ market, as Figure 6 shows. Prices for first homes are steady in Perth, which is now a ‘neutral’ first home buyer market, and rising slowly in Adelaide, which is a sellers’ market for first home buyers.

Housing prices in the flooded suburbs are now back to where they would have been had the disaster not occurred, and the time for Brisbane’s housing market to respond to the huge increases in demand from new households has finally arrived. Figure 6 shows that this could start within the next 12 months and that boom conditions will be evident two years from now.

Because the growth starts at the low-priced end of the market, it could remain hidden from view for some months as increasing sales at the cheaper end of the market cause a fall in the overall median sale price. When the Brisbane median house price starts to significantly rise, the boom will already be underway.

What could change this prediction?

This prediction assumes that the current population growth and movement trends will continue, that interest rates won’t rise, the availability of housing finance won’t deteriorate, and there will be no increase in the rate of new housing development in Brisbane. On the other hand, if Brisbane’s population growth rate rises further, the prediction could swing into effect sooner rather than later.

Every year since 2013, many experts have incorrectly predicted that the Brisbane property market was about to boom. More recently, some of them have thrown up their arms in confusion and given up on the city as a lost cause. Yet just as these experts are deserting Brisbane, my analysis shows that it is now primed to be the next capital city set to boom.

John Lindeman

John Lindeman

is director of innovative housing

market analysts Property Power

Partners, and author of

Unlocking the Property Market