I am amazed, and a little concerned, at the number of people in their late 40s or early 50s who come to me because they have suddenly realised their superannuation is not going to be adequate to fund a comfortable retirement.

They are anxiously hoping that the purchase of an investment property or two will help make up the shortfall. It can most certainly do that – but realistically, the time to start building an investment property portfolio is yesterday. Most of us don’t start thinking about this at a younger age because of bias.

When we think of the word ‘bias’, we immediately relate it to racial prejudice or one-sided coverage of political parties by the media. But there is a different kind of bias not many people are aware of: cognitive bias. This is an umbrella term for the many, many faulty ways we have of perceiving information through a filter of personal experience and preferences.

How bias impacts our decisions

Biases tend to be hardwired and unalterable – a part of human nature. It’s di cult to pin down exactly how many proven biases there are that cause us to think and act unwisely, but what they all have in common is that they lead us to making irrational judgments and determinations, while being totally ignorant of the fact that we are doing so.

Every cognitive bias exists as a mental shortcut that allows us to make decisions quickly and efficiently, because we don’t stop to consider all the available information. This saves us time and energy, so it’s easy to understand why biases exist and how they can be useful. However, these trade-offs lead to mental errors.

The field of cognitive biases is beyond the scope of this article, but there is one that is of particular relevance to investors. Everyday life can be full of self-control problems, which economists are fond of blaming on present bias. This is the tendency to overvalue immediate rewards at the expense of long-term intentions, a trait that can have big implications later on in life. This inclination suggests that when we have a choice between a pay-off today and a pay-off in the future, we will nearly always choose to have the pay-off now.

If you ask someone whether they would prefer to have $150 today or $180 in one month, most often they would choose the $150. Even though this means relinquishing a 20% return on investment – which is not the smartest financial move – it makes sense, because the question is removed from the present.

Now, let’s reframe it. If you ask that same person whether they would prefer to take $150 in 12 months’ time or $180 in 13 months, you’ll find they are overwhelmingly willing to wait another month for the extra $30. It’s still the same one-month waiting period; the only thing that has changed is the immediacy of the reward.

In an experiment conducted a few years ago to help people understand the importance of saving for retirement, participants’ future selves were made more realistic to them in the present. Their faces were digitally scanned and altered to create a realistically aged version, and they were then given a choice about how much they would allocate to their retirement.

Those who had viewed an image of their older selves opted to put more of their savings aside.

‘Handing your money to a stranger’

Hal Hirshfield, an associate professor of behavioural decision-making at UCLA, concluded that people were estranged from their future selves and were undersaving for retirement.

As he said, “Why would you save money for your future self when, to your brain, it feels like you’re just handing away your money to a complete stranger?” Without the connection to your future self, your brain acts as if that person is someone you don’t know and, to be honest, couldn’t give two hoots about.

This disconnected thinking makes it harder for us to undertake actions that benefit us in the long term, because the more your brain sees your future self as a stranger the less likely you are to make choices that will help you in the long term. Choices like yielding to temptation less often, procrastinating less, exercising more, and putting away more money for retirement.

Most people rarely, if ever, think about the ‘far’ future, about something that might happen 30 years from now. People commonly don’t expect to be alive then, so they simply don’t think about it. If you rarely think about the future, this is a surprisingly easy habit to fall into. Anybody who believes in preparedness knows the frustration of trying to convince others that the future is not at all secure, but present bias is innate behaviour that lulls us into distraction and leads to laziness and inertia.

Present bias doesn’t just exist in the world of experiments but predominates in the real world. People flagrantly undersave for retirement, even when they earn enough to be able to put substantial cash aside as savings after expenses have been met, or they work for a company that will contribute additional funds into retirement plans.

We already know that while people may be genuine in their intentions to save for retirement, their tendency is to satisfy their more immediate and short-term needs and defer long-term savings goals.

As individuals enter the critical savings period during their 30s and 40s, a period when they have the most valuable asset of all – time – and one that is often wasted, this stalling behaviour can be hugely detrimental. When it comes to retirement savings, there’s a big divide between planning to save and actually doing so.

Due to our increased awareness and understanding of genetics, healthcare, hygiene, diet, exercise and lifestyle effects, life expectancy in Australia has improved dramatically for both women and men in the last century. This means you have even more years of retirement living for which to plan.

What is going to get you comfortably through those retirement years? The government pension is incredibly meagre, currently at around $36,000 a year or $690 per week for a couple. And, sadly, your superannuation is probably not going to provide you with the financial comfort, security or even wealth you have some nebulous idea it will provide.

So, what can we do about this? In this article I’ve identified the problem that present bias leads us to: a short-term approach to retirement, resulting in inadequate resources to fund that retirement. What is the solution? Get started as early as you can!

Nigel Green, founder of independent financial consultancy the deVere Group, said: “Whatever situation you’re in, it’s never too late to start growing, maximising and safeguarding your retirement income – there are always things that can be done. But the time to act is now, as the longer you put off planning for your retirement, the harder it becomes.”

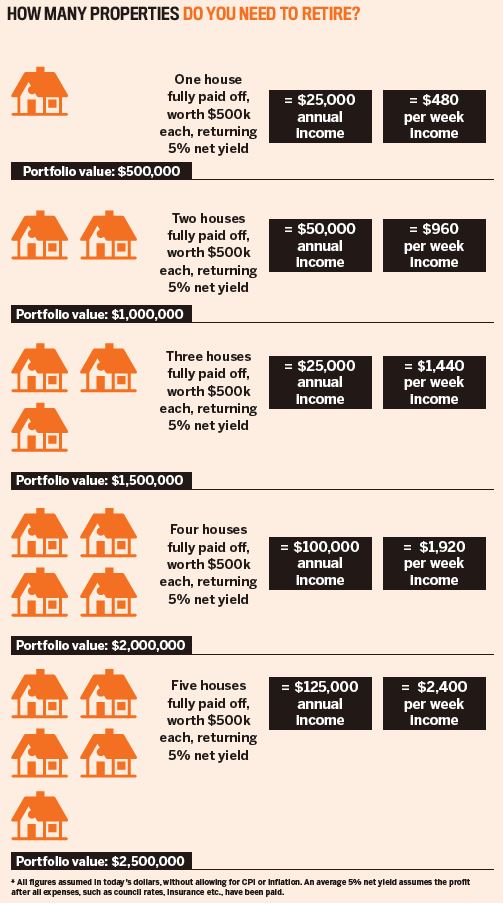

And so we come to property investing, which is hard to beat as a source of retirement income to supplement your pension and/or superannuation when you leave the workforce.

When we have a choice between a pay-off today and a pay-off in the future, we will nearly always choose to have the pay-off now

When you begin to think about how to plan and invest for retirement, you need to consider exactly what you want. Most people want a retirement free from hiccups; that is, without unexpected financial drains or disturbances.

Throughout their retirement years they would like to have independence through self-funding; a steady income stream; sufficient earnings to keep pace with expenditure; access to funds for emergencies or to assist family; to be protected from market volatility; and a minimum of negative growth.

A friend of mine thought he was sitting pretty when he retired with a $1m unencumbered principal place of residence and $500k in super. He said the day he went to see his financial adviser after he retired was the worst day of his life. (Note that I said after he retired; the conversation with his financial adviser would have been much better taking place before retirement!)

As he was a very active retiree, with a motorbike and pilot’s licence and a love of travel, he needed to plan for two phases of his future: those years when he would be most active with his biking, flying and travelling and thus need more funds; and the less active phase when he would have to give those things up due to fading eyesight, infirmity and so on and thus need less. It had never occurred to my friend that he needed to budget for both phases accordingly.

As we can’t accurately predict what age we’ll live to, we can’t know exactly how much income will be needed in retirement or how many investment properties that will equate to.

What we do have more certainty about is where we’re starting from – and the best place to start is by having a clear idea of your current position. The extensive research into cognitive bias has led to the realisation that the more information you have the more likely you are to make the smartest choices. It’s absolutely true that knowledge is power, and I am happy to have a discussion about incorporating investment property into an effective retirement plan.

As I previously stated, the time to act is now. While the thought of being proactive may set you a-trembling, facing retirement on an income of a few hundred dollars a week is an even more alarming scenario.

Philippe Brach

Philippe Brach

is the CEO of Multifocus Properties

and Finance and author of Creating

Property Wealth in any Market

Disclaimer: The advice in this article is a guide only. No person should rely solely on the contents of this article without also obtaining advice from a qualified building and pest inspector and/or solicitor.