Getting one's surplus cash flow working to either acquire property or pay down debt is all part of the property investment planning process.

Sounds easy enough – but how do you deal with a particular variable that has the power to strip away your surplus cash fl ow or add to it, when in reality you have no direct control over it? I’m talking, of course, about interest rates.

Factors that drive interest rate movements

To understand the whole interest rate dynamic, you have to get your head around macroeconomic policy, which is designed to drive economic growth to improve living standards, the ultimate goal of any government and democratic society.

Imagine two big levers that help control the economy. The hands on the first lever are those of the government, which is responsible for fiscal policy; in very simple terms this relates to managing the money they receive (taxes, duties, levies) and how they spend it (health, education, infrastructure, pensions). They are trying to balance this out each year to keep the economy growing and people employed.

If they don’t get enough revenue or if they promise too many services they can’t afford, they borrow money that one day they hope they will be able to pay back. One day!

The other big lever is monetary policy. It’s controlled by the central bank, in our case the Reserve Bank of Australia. The RBA is responsible for helping with the flow of money within the economy, and it does this by setting the cash rate – the rate at which they lend money to banks so banks can then lend to businesses and individuals – to stimulate or slow down the economy.

This is where interest rates come into play. If the RBA believes the economy needs a shot in the arm, it lowers the cash rate to encourage businesses to invest with the view to employing more workers to benefit the economy. A lower cash rate, if passed on to individuals, also has the potential to put more money in the pockets of borrowers because they are paying less interest. In this case the RBA is hoping the borrower will pay down some of their debt but also spend some of it in the economy, through retail or services, again increasing demand for employment and growing the economy.

However, if this lever is too stimulatory, then there is a danger that the economy will grow too quickly, causing inflationary pressures on the economy. If inflation gets too out of control, the value of things decreases in real terms and the value of money is worth less in real terms too.

Both the fiscal policy and monetary policy levers need to be prudently managed, which is a very difficult task when our domestic economy can be hit by external international factors outside of its control.

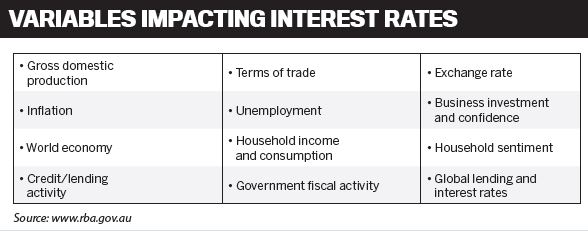

To help determine what cash rate to set, the RBA looks at money marketing indicators each month to decide whether the current rate is appropriate or needs to be adjusted. See the boxout below for a list of some of the most important variables – and for those of you die-hard stats folks, the RBA’s full monthly ‘chart pack’ can be downloaded from www.rba.gov.au.

"APRA may need to come up with some further interventions, as … investors still have considerable appetite for residential property"

Different drivers of fixed interest rates and variable rates

In simple terms, banks and retail lenders (those who lend to businesses and individuals) can source their money from deposits they take from savers, from central banks like the RBA, and from the international money markets.

The idea is that banks and lenders work out their cost of funds and when lending them out they put a profit margin on top of what they pay for

the money.

In the case of sourcing money for the variable interest rates, banks use a combination of the BRA cash rate and what they are paying out in interest to depositors, and maybe even for international money they are accessing on the short-term money markets, as an example to work out their cost of funds, to which they add their margin.

This interest rate is variable because the cost of this money can and does change on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. For the lender to be viable (or profitable) they need to adjust the rate accordingly to ensure they maintain a profitable margin for the so-called risk they are taking in lending out this money.

Therefore, when the RBA announces it has adjusted the cash rate higher, you can bet your bottom dollar the banks will react promptly to increase their variable rates. I just wish they were as prompt when the cash rate decreases, as history tells us they are a lot slower to move their variable rates down.

Furthermore, recent history also shows us they sometimes don’t pass on the full cash rate cut because it’s not the only component that makes up their funding costs – they need to look after their deposit customers too.

In the cast of fixed rates, banks will source money on longer terms, meaning they will source or raise larger sums of money for periods of three, five or 10 years, or possibly longer.

"When the RBA announces it has adjusted the cash rate higher, you can bet your bottom dollar the banks will react promptly to increase their variable rates"

They do this by issuing covered bonds, bank bonds or residential mortgage-backed securities. Given that this funding is over longer periods, this allows the bank to allocate these bulk funds for sale as fixed loans at a certain set interest rate.

Changes to pricing these fixed rate loans occur once the funding allocation is used up, and although banks are always trying to roll over funding to their best advantage, longer-term funding costs can and do change too. Such price changes occur based on global financial markets of the day and the investors’ appetite to actually invest in these bonds, in terms of the risk they take versus the return on their investment. This is why fixed rate pricing at the consumer level also changes from time to time.

Why do investors pay more than owner-occupiers?

Many investors rightly ask the question: why am I paying a higher interest rate than a homeowner for the exact same financial product? Furthermore, will this trend continue?

Politics, politics, politics (and add a dash of market manipulation in there by one of the regulators as well) starts to explain the answer to this question. Allow me to explain why the investor is the cause and why we have been caught in the crossfire.

The property market is red hot in Sydney, hot in Melbourne and Canberra, and warming up in Brisbane, Adelaide and Hobart. Property investors are also knee-deep in the action. In fact, based on historical activity, they are more active now than they have ever been, according to my research. One can put this down to historical low interest rates, a few years of uncertainty and volatility on the stock market, low returns from bonds and term deposits, and there you have it: all roads lead to investing in bricks and mortar.

The truth is, these current levels of activity are unsustainable. Based on historical and more recent history in other countries, if the housing market collapses, so does the overall economy. The RBA believes this to be true and it knows its cash rate settings are part of the cause, but it has a bigger job to do to stimulate the business sector to start borrowing and investing to create more jobs and reduce the spare capacity in our labour markets.

Therefore, it called in the cavalry in the form of APRA to intervene.

APRA put speed humps in place to slow down the banks’ lending in the investment space, advising them that they had to cap the growth of their investment loan books at only 10% per annum. The banks are owned by their shareholders and they expect a good return on their shares, but APRA’s invention threatened to hurt their profits, unless the banks tried to find more margin somehow.

This is where the politics came into play. To further stimulate the economy in mid-2016, the RBA dropped the cash rate. However, the banks didn’t pass on the entire cash rate to their variable interest rates, citing ‘getting the balance right between their deposit customers and their borrowing customers’ as the reason.

The opposition blamed the government for being weak in not getting a better deal for borrowers, so the government called all the CEOs of the big banks in for a catch-up in Canberra. (Got to be seen to be doing something, right!)

The bankers then had a problem: if they didn’t pass on any further cuts to borrowers they faced a further political and public backlash.

What to do? Well, the politicians don’t have as much of a problem with investors carrying the can, so the bankers, still looking for ways to counter the pressure on falling profits, introduced higher interest rates for property investors.

The politicians are happy, and APRA is happy because it’s a further disincentive for investors and in their eyes it’s helping to protect the housing market from moving too close to being a bubble.

What is interesting is that APRA may need to come up with some further interventions, as based on current market activity in early 2017 investors still have considerable appetite for residential property.

Where are interest rates heading from here?

Let me get my crystal ball out…In all seriousness, my read on interest rates is that they will not go any lower unless we see further risk around deflation. However, based on more recent business and consumer confidence and sentiment surveys – of markets other than Perth, and Darwin to a lesser extent – I think the monetary policy settings are already attractive enough for businesses to borrow and invest right now.

"These current levels of activity are unsustainable. Based on historical [events] and more recent history in other countries, if the housing market collapses, so does the overall economy"

Besides, I don’t want to see any further stimulatory pressure on the housing market.

At the time of writing, I don’t see interest rates going higher or lower this year, but rather remaining on hold until we see the spare capacity in the labour market improve and inflation back inside the RBA’s target range (2–3%). However, like any crystal-ball gazer, my only caveat is the global outlook around political stability and the USA’s protectionist policies and the potential impact on China exports. The follow-on effects will hurt the Australian economy on the downside and put pressure on the cash rate.

My more optimistic view is that the next rate movement will actually be up. So, if I was looking forward to the next couple of years, I would say that if our economy is travelling better than today we will see rates move off these current ‘high stimulus’ settings to more sustainable levels.

In terms of interest rates for investors, I would expect them to sit within a range of 4.5–5.5% for the next two to three years, and then start to move up in early 2018.

An ‘average’ for interest rates

If you buy shares in a company on the stock market based on the longer-term prospects and fundamentals of that business and its share price, then most would class you as an investor.

If you speculate on short-term price movements on the stock market, showing little interest in the company’s future, most would class you as a share trader.

In property, similar classes exist – a true property investor is one that invests in the long-term fundamentals of the location and the attributes of the property in question.

Yet there are others who attempt to pick the short-term pockets of the market they think will be instant winners, and they are best classed as speculators. One group is an active hands-on bunch; the other group is a more passive hands-off crew, relying on time to do the heavy lifting for them.

Those who are in the active camp, ie speculators, really don’t need to consider interest rates, as their endeavours are more transactional so interest rates don’t carry as much weight or influence in the decision-making.

For the passive long-game player, interest rates can and do play a real role in the overall cost of holding the property and keeping the cash flow flowing back to the investor over time. That is why it’s so important when crunching your long-term investment returns to try to establish a long-term benchmark interest rate to use in your modelling.

Too often people ask me what is really going to happen to interest rates, because they have got too excited or too greedy and overstretched themselves with the level of debt they are holding. This puts them at the mercy of any short-term rate movements and subsequently puts their whole financial future on the line. This is just plain dumb and far too dangerous in my view.

Since 1993, when the Reserve Bank was decoupled from direct government control to become an independent monetary policy setting institution, and up until before the GFC, residential mortgage interest rates have averaged around the 7.5% mark.

Post-GFC, we saw fiscal stimulus packages. Central banks pulled the monetary policy lever and dropped rates globally, all with the goal of trying to stabilise the whole money lending system and help avoid a global depression. In Australia, we followed suit and have now experienced interest rate levels we have not seen since the 1950s – absolute record lows with retail rates at the mid to high 3% level.

Again, do not be fooled by thinking that rates will stay this low forever, because if they do, it means our economy will be tanking and that is not good for jobs or long-term growth in property prices.

My view is that it will take a long time before we see rates at around the 7% mark, possibly one or even two generations, and it would mean the Australian economy would be tracking very well indeed if we did get to this level again in the next 10 to 20 years.

That said, don’t think that rates will stay below 5% for too long. If you want to ensure that you are a long-term passive property investor and one that can sleep well at night while managing your debt, work on using an interest rate level of 6.5–7%. The higher it is, the more conservative you are being, which can never be a bad thing – and then you don’t have to sweat the short-term interest rate movements.

When to fix your rates

Current interest rate settings are very attractive, and investors should be taking every step to ensure they are building up a nice offset or savings buffer for the rainy day that one day will come.

If you do the right thing and make sure you have provisions for changing rates, as well as any unforeseen events in your life, you are being very prudent. If you are able to amass a good-size buffer, then technically there may be less reason to fix your rate for any period of time.

"Do not be fooled by thinking rates will stay this low forever, because if they do it means our economy will be tanking – and that’s not good for jobs or long-term growth in property prices"

For me, one of the biggest reasons to fix your rate is to ensure a significant reduction in income for a period of time, most commonly in the event of starting a family. If you are lucky enough to be in a position to invest before the kids come along, then being able to fix a portion or in some cases the full amount of your loan for a few years before returning to work has merit. It can certainly help with cash flow planning during this period, when some other household costs are definitely changing.

For those who may not be planning kids, or are a sole household or on the other side of starting a family and have two incomes again, variable rates may be more prudent. This is especially true if they have done their cash fl ow models using 7% interest rates and can afford to invest in property in the short and long term. If this is the case, the vast majority of people should stay with variable rates as they often are priced lower than fixed rates, generally speaking.

I don’t know of too many property investors who can pay cash outright to build their property portfolio. If you are one of them, good for you!

As for the rest of us who have to borrow money to continue building our portfolios, interest rates are part of the process as they usually form the biggest cost on our journey to financial freedom. Having a healthy understanding of them will put you in good stead on your own journey.