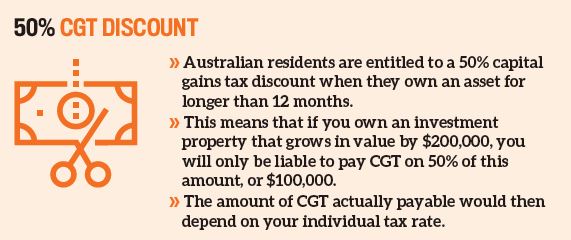

Investment properties are generally subject to capital gains tax (CGT), which is a tax levied against the profits you make on your investment when you sell.

Your CGT bill can be a substantial sum – sometimes, depending on the amount of capital growth, up to several hundred thousand dollars.

If the property is in your own name, your CGT bill is calculated at your individual income tax rate. For instance, if you earn $100,000 per year and pay tax of 37%, plus Medicare Levy of 2%, and your capital gain after discounts (see boxout p64) is $50,000, then you would add $50,000 to your income in the financial year that the property is sold.

The six-year rule applies to your principal place of residence, which is generally exempt from any source of tax, whether it’s land tax or capital gains tax

You would then pay CGT at a rate of 39% (Medicare inclusive), which would amount to $19,500.

The one property that you do not have to pay CGT on is your primary place of residence.

The good news for property investors is that there is also a specific rule that allows some property owners to convert their own home into an investment property by renting it out, and avoid paying CGT on the profits when it’s eventually sold. This is called the six-year rule.

What is the six-year rule?

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) explains that the six-year rule allows you to treat a dwelling as your main residence for up to six years after you have moved out, if it is used to bring in income. This means you won’t have to pay any CGT if you sell the property within six years of moving out of the home.

“The six-year rule applies only to your principal place of residence, which is generally exempt from any source of tax, whether it’s land tax or capital gains tax,” explains Ed Chan from Chan & Naylor.

“Once you rent out your home and get a tenant, you generally have to pay capital gains tax on it – unless you move back into it within six years. Once you move back in, you then get rid of your capital gains tax obligations related to the property. You can move out again later and rent it out, and as long as you’ve moved back into the property within the next six years, then you’re exempt from capital gains tax.”

In other words, you can move in and out of the property multiple times, and provided the length of time that you’re away never exceeds six years, you’ll never have to pay CGT.

However, there are some conditions to this rule.

Firstly, you must genuinely live in the property first in order to enact this rule. You can’t claim an investment property as your PPOR if you’ve never actually occupied the property yourself.

Also, during the six-year period, you are not allowed to treat another property as your official main residence in the eyes of the ATO. If you are renting or living with family, then you’re all set, but if you purchase another home to live in, you’ll have to decide which of the two properties to declare as your PPOR.

When is CGT payable?

Although CGT can be an expensive burden, many investors forget that payment of capital gains tax is not due until you lodge your tax return for the financial year in which the property is sold. “If you sold your property in January, you would have to lodge a tax return after 30 June. Your tax year ends in June, and depending on when you individually have to lodge your return – everybody is different – you might have to lodge your return by 31 October, or it might not be due until February or March the following year,” Chan explains.

“You’ll then have some time to pay the tax bill after the return has been lodged. To work out when you have to lodge a return, ask your accountant.”

In a nutshell, the six-year rule allows you to move out of your residence, live somewhere else (provided you don’t own the property) and rent out your former home, then sell it before the six-year period is up without having to pay CGT. You can also move back in and then rent out the property for further periods, provided you don’t rent it out for longer than six years at any given time.

Property investors should note that this rule was designed to assist homeowners who genuinely need to move out of their home; it was not designed as a tax avoidance strategy for investors.

“The difference between tax planning and tax avoidance largely comes down to intent,” the ATO explains.

“Once you rent your own home out and get a tenant, you have to pay capital gains tax on it, unless you move back into it within six years” Ed Chan

“Tax planning is organising your … tax affairs in the most tax effective way within the intent of the law. In contrast, tax avoidance schemes involve the deliberate exploitation of the tax system.”

If in doubt about the specific tax obligations and deductions available to you as an investor, contact the ATO or your accountant.